Tech

Seven planets are lining up in the sky next month. This is what it really means

Stargazers will be treated to a rare alignment of seven planets on 28 February when Mercury joins six other planets that are already visible in the night sky. Here’s why it matters to scientists.

Peer up at the sky on a clear night this January and February and you could be in for a treat. Six planets – Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – are currently visible in the night sky. During just one night in late February, they will be joined by Mercury, a rare seven-planet alignment visible in the sky.

But such events are not just a spectacle for stargazers – they can also have a real impact on our Solar System and offer the potential to gain new insights into our place within it.

The eight major planets of our Solar System orbit the Sun in the same flat plane, and all at different speeds. Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun, completes an orbit – a year for the planet – in 88 days. Earth’s year, of course, is 365 days, while at the upper end, Neptune takes a whopping 60,190 days, or about 165 Earth years, to complete a single revolution of our star.

The different speeds of the planets mean that, on occasion, several of them can be roughly lined up on the same side of the Sun. From Earth, if the orbits line up just right, we can see multiple planets in our night sky at the same time. In rare events, all the planets will line up such that they all appear in our night sky together along the ecliptic, the path traced by the Sun.

Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn are all bright enough to be visible to the naked eye, while Uranus and Neptune require binoculars or a telescope to spot.

In January and February, we can witness this event taking place. The planets are not exactly lined up, so they will appear in an arc across the sky due to their orbital plane in the Solar System. During clear nights in January and February, all of the planets except Mercury will be visible – an event sometimes called a planetary parade. On 28 February, though – weather permitting – all seven planets will be visible, a great spectacle for observers on the ground.

“There is something special about looking at the planets with your own eyes,” says Jenifer Millard, a science communicator and astronomer at Fifth Star Labs in the UK. “Yes, you can go on Google and get a more spectacular view of all these planets. But when you’re looking at these objects, these are photons that have travelled millions or billions of miles through space to hit your retinas.”

Tech

‘Dark oxygen’ mission takes aim at other worlds

Scientists who recently discovered that metal lumps on the dark seabed make oxygen, have announced plans to study the deepest parts of Earth’s oceans in order to understand the strange phenomenon.

Their mission could “change the way we look at the possibility of life on other planets too,” the researchers say.

The initial discovery confounded marine scientists. It was previously accepted that oxygen could only be produced in sunlight by plants – in a process called photosynthesis.

If oxygen – a vital component of life – is made in the dark by metal lumps, the researchers believe that process could be happening on other planets, creating oxygen-rich environments where life could thrive.

Lead researcher Prof Andrew Sweetman explained: “We are already in conversation with experts at Nasa who believe dark oxygen could reshape our understanding of how life might be sustained on other planets without direct sunlight.

“We want to go out there and figure out what exactly is going on.”

Tech

‘Sadbait’: Why algorithms, audiences and creators love to cry online

People say they don’t want to be sad, but their online habits disagree. Content that channels sorrow for views has become a ubiquitous part of online culture. Why does it work?

Whether you’re a state-sponsored misinformation campaign, a content creator trying to make it big or a company trying to sell a product, there’s one proven way to win followers and earn money online: make people feel something.

Social media platforms have been called out for incentivising creators to make their audiences angry. But these critiques tend to focus on content designed to infuriate people into engaging with a post, often called “ragebait”. It’s earned considerable scrutiny and even shouldered some of the blame for political polarisation in recent years – but rage isn’t the only emotion that leads users to linger in a comments section or repost a video.

The internet is flooded with what some call ‘sadbait’. It gets far less attention, but some of today’s most successful online content is melancholy and melodramatic. Influencers film themselves crying. Scam artists lure their victims with stories of hard luck. In 2024, TikTokers racked up hundreds of millions of views with a forlorn genre of videos called “Corecore”, where collages of depressing movie and news clips lay over a bed of depressing music. Sadness is a feeling people might think they want to avoid, but gloomy, dark and even distressing posts seem to do surprisingly well with both humans and the algorithms that cater to them. The success of sadbait can tell us a lot about both the internet, and ourselves.

Entertainment

How venomous caterpillars could help humans design life-saving drugs

Some species of caterpillar come armed with powerful venoms. Harnessing them could help us design new drugs.

When you think of venomous animals, caterpillars probably aren’t the first thing that comes to mind. Snakes, of course. Scorpions and spiders, too. But caterpillars?

Yes, indeed. The world turns out to be home to hundreds – perhaps thousands – of species of venomous caterpillars, and at least a few of them pack a punch toxic enough to kill or permanently injure a person. That alone is reason for scientists to study them. But caterpillars also contain a potential windfall of medically useful compounds within their toxic secretions.

“Will we get to the stage where we’ll be taking things from their venoms that are useful? Definitely,” says Andrew Walker, an evolutionary biologist and biochemist at the University of Queensland, Australia. “But there’s a lot of foundational work to do first.”

Caterpillars are the larval stages of the insect order Lepidoptera, the butterflies and moths. It’s just one of many animal groups with little-known venomous members. (Venoms are toxins that are deliberately injected into another animal, while poisons sit passively in an organism’s body, waiting to sicken a potential predator.) By biologists’ best estimate, venoms have evolved at least 100 times across the animal kingdom.

Many venoms are complex, some containing more than 100 different compounds. And they’re also strikingly diverse. “No two species have the same venom arsenal,” says Mandë Holford, a venom scientist at Hunter College and the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. “That’s why it’s important to study as many species as we can find.”

-

Entertainment5 months ago

Entertainment5 months agoEarthquake scientists are learning warning signs of ‘The Big One.’ When should they tell the public?

-

International5 months ago

International5 months agoTarar accuses Imran Khan of conspiring with Faiz Hameed to destabilise Pakistan

-

International3 months ago

International3 months agoPTI Announces Not to Boycott New Committees

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoMajor Corruption Scandal Uncovered at WASA Multan: Rs1.5 Billion Embezzlement Exposed

-

Business5 months ago

Business5 months agoThe Impact of QR Codes on Traditional Advertising

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoHigh Court Blocks MDCAT Merit List Amid Controversy Over Exam Error

-

Business5 months ago

Business5 months agoThe Benefits and Problems of International Trade in the Context of Global Crisis

-

International5 months ago

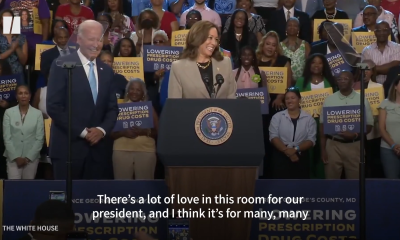

International5 months agoGOP Pollster Spots Harris’ ‘Tremendous Advantage’ Over Trump: ‘Does He Want To Lose?’